Tunnel Vision x2

Tunnel Vision – More Last Spikes – Two Stories – Two Railways

by Back Roads Bill

Sometimes after reading superlatives like the biggest or best you get thinking about other things that may be as equal.

We know the well-known black and white photograph featured in the introduction of Pierre Berton’s ‘The Last Spike.’ All those men with the long beards and moustaches and tall hats. It was the ceremonial driving of the CPR’s last spike into the rail bed in the Craigellachie Mountains within British Columbia’s interior. Some of the major figures of Canadian history are there, Donald Smith, William Van Horne and Sir Sandford Fleming. But there were other “last” spikes because the railway building era was divided into two sections and there was another railway that was catching up.

Then after reading more about this important event you wondered if there are railway tunnels in eastern Canada. We most often think of the colossal tunnelling effort through the western mountains by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) syndicate of the late 1800’s. There are a few railway tunnels in eastern Canada. There are two tunnels to visit and at least one more commemorative cairn.

Tunnel One – CPR

Building the CPR was more about achieving nationhood for Canada in the 1880s – coast to coast – than it was about building a railway as an elegant and showy operation. A lot of money and a lot of rock were eaten to build an all-Canadian route, rather than building through easier terrain in the United States as original CPR railway syndicate members would have preferred. The Lake Superior section became costly, problematic, and construction was generally “slow” to complete. The cost of dynamiting and moving rock was appalling. The destinations you will visit reflect the most challenging barrier of the day.

At the Jackfish tunnel you can see and appreciate how much of the line was chiselled into the rocky shore – using the technology of the1880’s. Lake Superior is always close at hand. Imagine what the terrain here was like before the railway came and how much rock had to be moved by horse and manual labour in the course of drilling and blasting the tunnel. Then the rock and fill had to be moved in to provide a roadbed suitable for laying track.

Think of the work involved in building a railway line in the 1880s. Between Marathon and Terrace Bay you see how most of the hills are granite with just enough soil to support trees. When you consider that railways usually rise a maximum of 2.2 units vertically for each 100 units travelled horizontally the answer for early civil engineers was the proposed railway line had to “hug” the shoreline. The grade over distance had to be gradual.

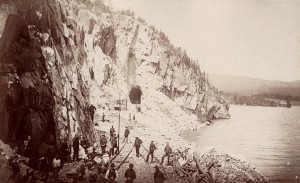

Instead of an impossible one kilometer bridge, the train travels 5 kilometers (three miles), close to lake level, around Jackfish Bay. As you watch a train go by it is a very impressive experience because the train is dwarfed by its environment. The entire view probably won’t fit into your camera’s viewfinder. As you walk this section the archives tell us this was one of the most expensive and difficult sections of railway construction. You can georeference this historic photo of the Jackfish Bay tunnel with your own candid shot at UTM 16 U 502767 5406904 or N 48 48.907 W 86 57.739.

This is the from west to east approach to the tunnel, completed under R. G. Reid’s Jackfish contract of the C.P.R., 1884 construction crew; Henry and Norman Photographers, black and white print; reference code: C 224-0-0-2 Archives of Ontario, I0016410.

In summer of 1884 there were 15,000 men and 4,000 horses working on the North Shore of Lake Superior. Records indicate the workers consumed twelve tons of food per day and four tons of tobacco each month. It is amazing to consider not one locomotive train, steam shovel or power drill was utilized on this rugged landscape. It was indeed labourious. The area near Jackfish, including three railway tunnels, cost $1,200,000 in capital dollars of the day.

As a bonus you will want to walk a short distance westwards, to Noslo a little less than one kilometre, from the Jackfish Bay tunnel to one of those historic events we take for granted. (Noslo is spelled backwards, really for a surname Olson, a railway management type). Many of the sidings and whistle stops are spelled backwards, one near North Bay is Yellek, really for one of the foremen, with a surname, Kelly.) For the railway construction crews of the day it was a milestone, an accomplishment. This section from Montreal to Winnipeg section was driven at mile 102.7 in May of 1885. You will want to read the inscription on the plaque. It is the “last spike” in completing this eastern section of railway construction. You will be near N48° 48.517’ W86 ° 58.488’ or 16 U 501851 5406182.

The inscription reads: Driving the Last Spike Between Montreal & Winnipeg, May 16th, 1885…” Present was Colonel Oswald of the Montreal Light Infantry, along with his troops on the first train eastwards. They were returning home from the Riel Rebellion in Saskatchewan. It was one of the major factors in completing this difficult stretch of railway construction. These tunnels are more than just symbolic they link our historic events.

Here is your chance to experience some early Canadian heritage part of bringing Canada together as a nation. For the Jackfish tunnel you will travel west of Marathon or east of Terrace Bay. From both directions Highway 17 descends from high relief down towards Jackfish Lake. There is a straight stretch of highway that parallels the lake. There are a couple of motels along this stretch of highway.

At the east end of this stretch look for unmarked road at 16 U 504220 5407585 or N48 49.274 W86 56.551 which leads to a small picnic area. If you have a canoe or small boat you could launch here and move towards the Jackfish Bay railway bridge which leads to the bay and Lake Superior. This would be less than one kilometer.

Without a small boat or canoe stay on the road and drive past some camps/cottages. The road is good. Drive on as you approach the first power corridor the road starts to become a little less travelled. (This is where we park…but you can drive on).

The walk along the road to the next power corridor and access to the railway tracks is less than one kilometer. At the second power corridor look to the right or westwards you will see the railway tracks.

You walk the railway right of way northwards, the line veers westwards and crosses the Jackfish Bay railway bridge. From the start of the railway tracks to the tunnel is just more than another one kilometer. At the bridge you will see Jackfish Lake and Highway.

Tunnel Two – CNR

You can walk through a 300 m abandoned rail tunnel that is one of the longest in eastern Canada.

Construction of the transcontinental railway spurred the birth of Canada; in fact, all of North America was undergoing change in the 19th century. Immigrants, especially Europeans, poured in to settle the land. There was a need for more than one national railway.

Canadian National Railway (CNR), incorporated on June 6, 1919, took form through a series of mergers between 1917 and 1923, uniting several older and financially troubled railways, many of which had been built between 1850 and 1880.

By 1919, the Intercolonial, Canadian Northern, National Transcontinental and Grand Trunk Pacific had become part of a government railway system known as the CNR. It was during this time the Kinghorn sub line from Longlac to Nipigon was constructed.

During the 1980’s railways in Canada felt the impact of the USA-Canada Free Trade agreement and a period of deregulation and downsizing followed. Some short lines were abandoned. The last train to pass through this beautiful section of track was in May 15, 2005, and by May 2010 there was nothing but a roadbed and ties to remind us of the line.

From Nipigon drive east on Highway 11/17 and then turn left onto Highway 11. After you drive for about 53 km, watch on the right (east side) for a utility building where you can park (N49° 25.502’ W88° 07.516’ or WGS 84 16 U E418399 N5475315). If you reach the turnoff to the Rocky Bay First Nation in MacDiamid you have gone too far, eastward, by about 1.5 km. From your parking spot cross the highway and walk 50 m down the road to Jumbo’s Cove. Turn right (north) when you reach were the tracks were. You will soon see the entrance to the tunnel. It’s a good idea to bring a flashlight.

We don’t have the opportunity to go through tunnels much. So take the opportunity and have a look at our heritage.